When I started my PhD, I had a big misconception about what the phrase ‘state-of-the-art’ meant. In my mind, a state-of-the-art vehicle was the Mach 5. A state-of-the-art facility was one with a lot of glass walls, researchers in white coats, and floating computers that gave sassy, yet sage, advice. State-of-the-Art was synonymous with The Future.

I have since learned that this is not correct.

Not entirely, at least. For me, The Future was complete. Things worked. Technologies were flawless. Since I’ve become involved in robotics, I know now that State-of-the-Art, especially in these fields, is often far from achieving this lofty goal. Things break. Solutions are hacky.

This is in no way a criticism of the robotics community; the science that has been produced in the past couple of years is amazing, and often a strong prediction of what The Future will hold. Yet the fact of the matter is, creating robotic systems is hard. Design is hard. Perception is hard. Path planning is hard. These are all active fields of research, and there is no perfect solution to any of them.

However, research and the real world often tend to be two very different things. AI is big business, and this economic boom has accelerated the development of new technologies. These, in turn, create even greater economic demand. It’s a cycle that we’re trying to harness at Replica Labs: business begetting tech, begetting business. However, as discussed in Part I, important players in this field (research and business alike) are voicing real fears about the pace of progress, mainly that we’re going too fast to truly understand the implications of what we are creating. To better know these claims, I believe it’s important to realize the state of AI now; that way, we can make a more educated prediction on what we might realistically expect.

The Buildup: Parallel Processing and the Algorithms They Love

Imperative to this conversation is what powers this AI takeover: parallel processing through Graphics Processing Units, or GPUs[1]Sorry if I dumb this down too much; GPUs are incredibly popular, but I realize that might just be with a niche group. All of robotics is a niche, to be perfectly honest.. GPUs are parallel programming to the extreme; while CPUs - Central Processing Units - commonly have 4-16 cores, allowing for 4-16 simultaneous calculations, beefy GPUs can have over 3000 cores, allowing for unheard-of computation speed. This kind of capability has been especially useful in computer graphics, where each pixel in an image can be changed at the same time, but researchers have begun to design their science around this massively-parallelizeable structure. Calculations used to take so long on CPUs that entire branches of math were developed to compensate, usually sacrificing mathematical accuracy to cut down on computation time. Now, algorithms are designed with GPUs in mind, and boy has it been worth it. Mythbusters explain it best:

Done right, GPUs can whittle down calculations that took days into a single afternoon. GPUs have gone beyond ‘graphics processing’, and now allow researchers to perform real-time physics simulation, real-time control, real-time speech analysis. GPU programming has hit the mainstream, but more importantly, programmers have finally learned to harness that power effectively.

The Here and Now: Prediction and Control

This newfound computation speed is allowing for things that weren’t quite possible a decade ago. One of the most striking examples here is the advent of the self-driving car. Cars that know not only where they need to go but also how to get there might seem like an amazing trick (or a one-way ticket to the ICU, depending on your technological stance), yet the speed of GPU processing, along with a lot of smart code, is making it happen. Tesla even announced a future over-the-air update that adds fully autonomous driving to their Model S. This feat was powered by a whole lot of parallel algorithms and, what else, the high-performance GPUs Tesla has in every car, compliments of a partnership with NVIDIA. Given that the Tesla is virtually a computer on wheels, this kind of hardware is not only convenient, but also vital for the safety of the passengers inside. Other self-driving cars share a similar story; GPUs and parallel algorithms allow an autonomous machine to both perceive and act upon their environment.

That example aside, cars have a long way to go before they’re turned into hyper-intelligent rolling doom machines. Here’s NVIDIA CEO Jen-Hsun Huang[2]Does anyone else think he sounds like Nicolas Cage? He makes his appearance about halfway in, for reference; you be the judge. showing off their new vehicle-embedded street object identification system.

It knows cars. Not a lot, just mainly cars, which is actually damn impressive, but still not really what you would consider a super-human sort of intelligence. Yet that video - that video - is the kind of science that strikes fear into the hearts of AI ethicists everywhere.

The Scary Part: Machine Learning

If you actually played the video above, you probably heard phrases like ‘deep learning’ and ‘neural nets’. These are all different parts of one big concept: Machine Learning. In my mind, the development of advanced machine learning is one of the most transformative achievements of our time. Put simply, machine learning makes sense of vast amounts of data for use in more abstract processes. For example, a good ML process can use all of those cat videos on YouTube to figure out for itself what a ‘cat’ is, and then use that info to identify cats in the future. I hope this doesn’t sound too simplistic, because the process of teaching a computer ‘cat’-ness is difficult, to say the least (though Google has done exactly that).

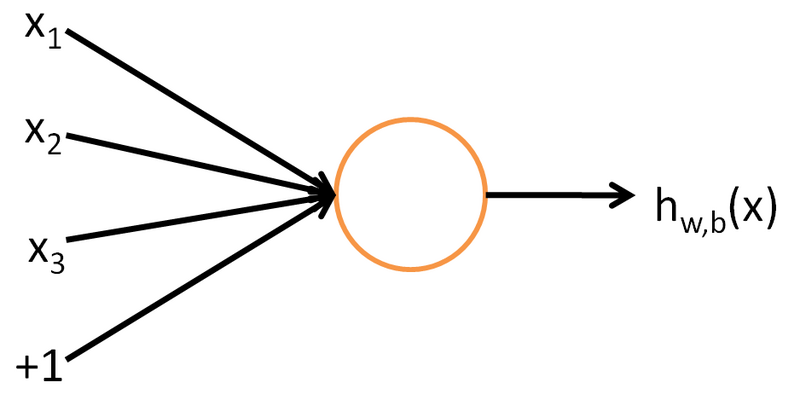

Machine learning as a field has been around for a while - papers date back to the ’50s - but ML in its current form has existed for only a couple of decades, with the maturation of neural networks. Neural nets are just a statistical method of finding patterns in large swaths of data, the design of which was originally inspired by the way your optic nerves communicate images to the brain. In its most basic form, neural networks use a non-linear equation of some sort to map a function from data (input) to result (output):

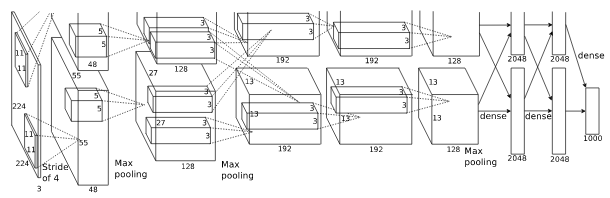

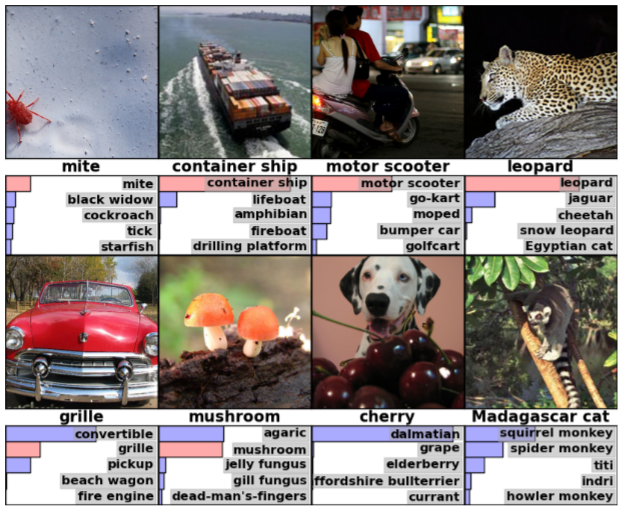

A perfect example of the State-Of-The-Art here lies in a paper by Alex Krizhevsky called “ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Nets”. It takes the above simplistic, straightforward model and just absolutely tears it up[3]Mathematically speaking.. What was once a quaint input-output is now an incredibly dense network of connections, all resulting in a complete and sophisticated way of mapping images to their identifying label.

The picture does not do it justice, but suffice to say, this system took days to process, or train, even when designed with GPUs in mind. It makes sense now why this type of network is ‘deep’; it’s layers upon layers, and the connections are too numerous to count. AlexNet, as it’s coloquially named, was one of the most successful image identification systems made, and many systems since have been based on this work. Looking at AlexNet’s initial labeling results below, even the missed classifications are pretty honest errors.

This kind of statistics is impressive in itself, but it gets even crazier when you realize that deep neural nets don’t even need to know what they’re learning. When I mentioned Google’s cat identification project using YouTube videos, it’s important to realize that they never told their system what a cat was.

Never mentioned it.

And yet, when asked for the strongest ‘cat’-like classifier when given a cat-like image, here’s what it came up with:

That is a damn creepy cat… but it’s definitely a cat, and that’s even more unnerving. The Google researchers that helped train this network were looking for what they called a “Grandmother Neuron”, or a classifier from a neural net that captured the essence of what an object was. Given the thousands (millions?) of cat videos this deep neural net was subjected to, this is the Grandmother Neuron that best described whatever was in all of these videos. Again, it was never told what a cat was; it just found a lot of different examples of the same thing, and used this to relate all the things together. That thing just happened to be a cat.

This ability to make sense of the world without human interference makes Machine Learning processes so powerful, and at the same time, so frightening. It’s easy to take the results of these experiments and extrapolate the horrible things that computers could do once they start interpreting beyond what’s presented at face value[4]Insert creepy cat face pun here., and I don’t blame anyone who thinks that way. However, I personally have a hard time seeing this progress as a harbinger of robotic doom. ML is, at its core, just a tool to aid in other tasks, whether those tasks are benevolent or malevolent; revolutionary technologies of the same magnitude often don’t posess a morality component embedded in their design[5]GPS, Radar, nuclear energy, social media, furbys, etc.. Yet the self-teaching aspect of this brand of AI, perhaps, makes the stakes a little higher.

This is the core of the argument against the unchecked development of artificial intelligence. Advocates argue that technology will soon become so advanced - even in our lifetimes - that to ignore its morality would do much more harm than good. If one’s goal is to make a life-like machine, one has to think about what happens when that goal is realized, and it can seemingly ‘live’ on its own, decide on its own, make mistakes while self-correcting all the while. What will it see as the right choice, when faced with a new ‘training’ task, if morality might come into play? In this light, the fears of Elon Musk, Bill Gates, and Stephen Hawking make a bit more sense. There has to be some system of checks and balances during this phase of AI research, or else the wrong move might be made so easily.

The (Realistic) Future of AI

BUT LET’S BE REAL. AI is still nowhere near human intelligence. And I say this with all due respect, as an avid robotics researcher and enthusiast. For proof of this, look no further than Amazon’s Picking Contest, which challenged participants (i.e. entire robotics labs) to find the most efficient way to

- Find an item

- Take it off a shelf, and

- Put it in a box

From a robotics standpoint, this process is hard to get right, yet it’s so simple compared to what a human might be able to do. There are upsides and downsides to both people and robots (one gets tired, the other breaks), but the cognitive difference is hopefully clear[6]It actually was a pretty cool contest..

By the way, this challenge is one of the market incentives that push this field of research to progress as fast as possible, directly contradicting the “Let’s think about this” attitude that many now advocate. Tons of money is funneled into machine learning and robotics by big corporations hoping that the next big thing will be their next big thing[7]Crazy Cat Generator! powered by Under Armour. which, to be fair, is something I would do if I was a big corporation. But I also think that the research community can still very much afford to push the State Of The Art, because a self-driving car does not a human mind make. I would fear dumb AI; I don’t want a stupid hunk of bolts driving me around, if you get my drift[8]My tokyo drift! I’m so sorry..

I have no doubt that the ethics of AI will become crucial in the near future. We just might be jumping the gun a bit. As AI evolves, we will evolve as well, learning how to handle that which can define itself. Whether you like it or not, though, robotics research will only accelerate from this point on; it can’t be stopped. To paraphrase the great Dr. Ian Malcolm: AI, uhh, finds a way[8]“Clever Perl…”.

I found/rediscovered some pretty cool sources while researching this article. If you’re interested in learning more about this kind of stuff before it learns too much about you, check these out:

- The History of Artificial Neural Nets - as opposed to Biological Neural Nets. It’s Wikipedia, yeah, but informative.

- Stanford’s Machine Learning Course - Taught by Andrew Ng, a powerhouse in his field.

- Stanford’s Unsupervised Feature Learning and Deep Learning tutorial - Builds up the concepts and the mathematics for much premium understand.

- Neural Networks, Manifolds, and Topology - An interesting graphical interpretation of deep neural nets.

- BONUS! MarI/O - Machine Learning for Video Games - You made it all the way through this article! Have a self-learning Mario-bot.

- BONUS 2! Learnfun and Playfun - More excellent video game learning.